City of Chicago Enlists ID Students to Aid in Parking Ticket Reform

In the summer of 2018, an investigation by ProPublica Illinois revealed thousands of Chicagoans, most from low-income and minority neighborhoods, were forced into bankruptcy after debts caused by parking tickets and other non-moving traffic offenses. A later joint report with WBEZ further revealed a pattern of accruing fees and, in many instances, repeat tickets for the same offenses, leading to a debt spiral.

One of the largest causes of this compounding debt was the $200 ticket for offenders who didn’t display up-to-date city stickers on their windshields. In many cases, individuals were given multiple tickets for this, and when tickets weren’t paid on time, those fees would double. The report found that approximately 500,000 Chicagoans had unpaid city sticker tickets.

In light of the revelations, the city has revised some of its practices, including new reduced term city stickers, implementing a city sticker amnesty month and debt forgiveness program, and lowering the bar for residents to get into payment plans. The findings also led the city to create the Fines, Fees, and Access Collaborative, a group composed of city departments, community groups, elected officials, and academic institutions, including Illinois Institute of Technology’s Institute of Design (ID).

The partnership began in the summer of 2019 when the city sent representatives to ID Design Camp.

“Having academic partners pushes us to think outside of the box. That’s especially from the user end, which I think is really important for the government to look at more,” says Chicago City Clerk Anna Valencia.

Led by ID Professor Mark Jones, a class of 18 students interviewed roughly 60 Chicago residents to learn more about their interactions with the city regarding parking tickets. Students found many vocal residents bemoaning a lack of clear and easy-to-access information from the City of Chicago.

“One thing that came through is how much people rely on word of mouth, and that the official channels where people are supposed to learn things aren’t effective. But word-of-mouth isn’t always accurate,” says Jones. “I think residents—particularly in low-income neighborhoods—feel as though they’re not being taken care of well. They feel as though the city is not trying to prevent them from getting into trouble and that they’re trying to get you, whether it’s from old signage or unclear rules.”

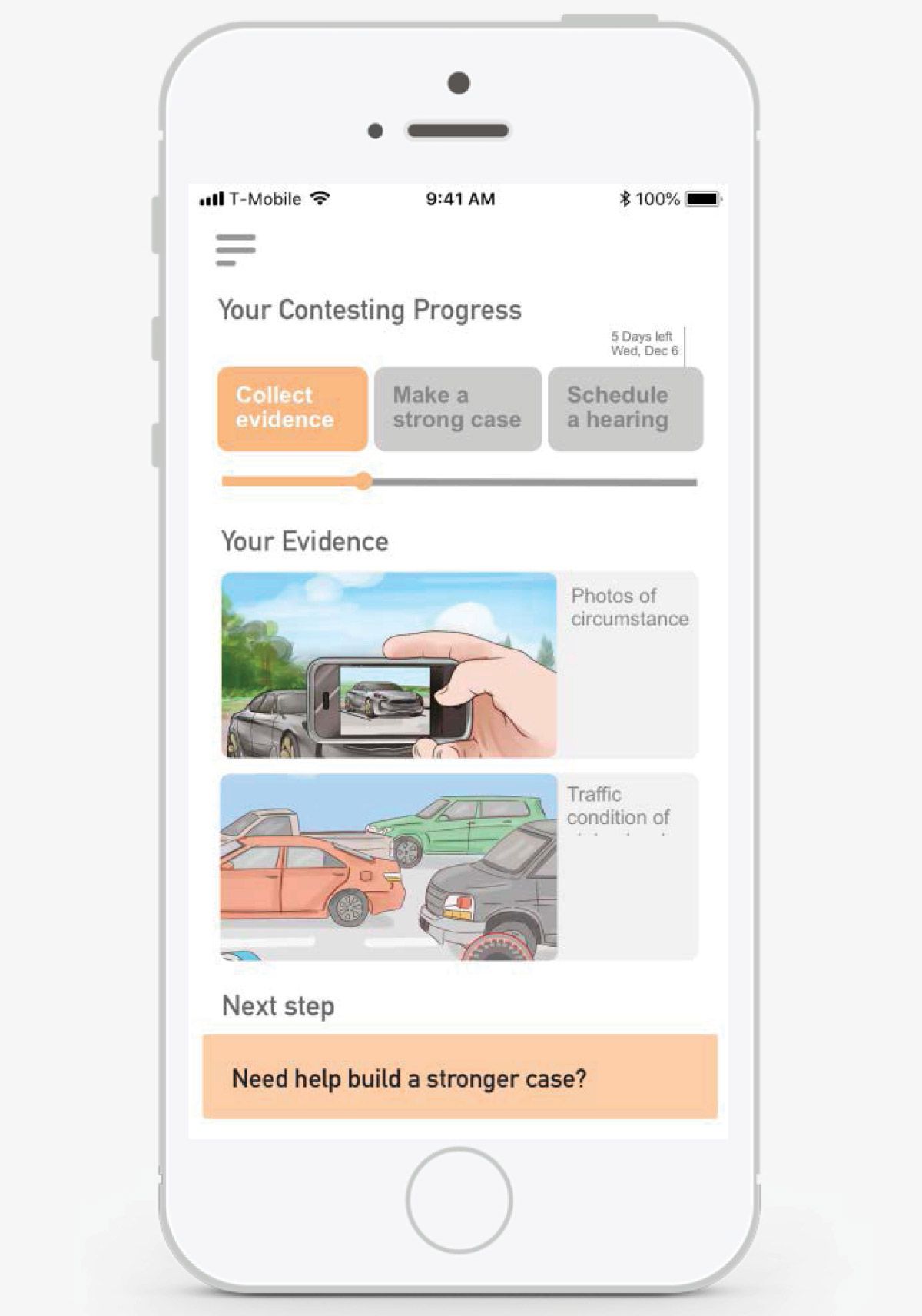

As such, Jones and his students honed in on a suite of solutions to improve communication between the city and citizens, help more drivers comply and avoid future tickets, and to build trust between the two. One example, which taps an easy-to-use mobile platform, is a “Tailored Ticket Roadmap.” This online portal graphically breaks down how much money an individual may owe and important dates—for contesting or when a ticket may double, for example—to offer residents a better sense of how to approach their debt.

“The current ticket system is such that each ticket is its own entity. People with multiple tickets can’t get a sense of the bigger picture. [The Tailored Ticket Roadmap is] a response to what we heard from people dealing with the city systems,” says Jones. “As good designers [the students] responded with something that’s easier to navigate and understand.”

Similarly, a “mobile lawyer” program could provide unfairly ticketed individuals—especially lower-income individuals who may not otherwise have the resources to challenge a ticket—with guidance on how to contest.

“If you are not as educated or in a lower income bracket you might not be aware of [how to contest], or you might be scared and just pay [a ticket] even if you don’t have the money, and that’s wrong,” says Valencia.

Another proposed idea is a text-alert system, where residents can text the city to receive reminders about when they need to move their cars in certain parking zones. This would help alleviate issues with confusing or unclear signs or even simple forgetfulness that might result in a ticket. Valencia says this program has particular promise.

As for city sticker compliance, ID developed an old-school solution: gas station signs. Many respondents to ID’s surveys said that, as newcomers to the city, they didn’t realize Chicago requires car owners to display city stickers—unless another local resident told them or they received a ticket. By putting signs in the one place all vehicle owners need to go, the city can better disseminate its message. While the students only tested the signs at gas stations, they also recommended installing them at Secretary of State offices and car dealerships.

For Chicago to completely revise its ticketing practices, it will need to continue on its trajectory of instating new policy reforms and ordinances. Still, both Jones and Valencia believe clearer and more accessible communications can ease the burden on lower-income citizens and help restore trust between city hall and Chicagoans.

“The solutions the students came up with are a mixture of preventative measures, as well as those that say, ‘If we made a mistake, we want to help fix the mistake,’” says Jones. “I think those are both good approaches that would say that the city is trying the best it can.”